Chapter 02 - How do hurricanes form?

The science behind hurricanes

Have you ever boarded an airplane and suddenly it shakes so much that you can't let go of the armrest? This is how it starts Atmospheric Turbulencethe new Canal Meteo podcast hosted by meteorologist and geographer Albert MartinezThe program, which invites us to discover the best kept secrets of meteorology, with a special focus on hurricanes.

Important points

- The science behind hurricanes

- In this episode

- Hurricanes, squalls and tornadoes: why are they not the same?

- The origin of the name "hurricane": deities, myths, and power.

- Where are they formed and how do they move?

- The monster's fuel: the ocean

- Sahara dust: an invisible enemy

- The role of climate change

- A storm can turn the world upside down

In this second episode we explore the science behind hurricanes with:

- Eduardo Rodriguezoceanographer, explains how ocean heat fuels cyclones and why the timing of the season responds to marine energy cycles.

- Kamila Dazaproducer and editor of the program, takes us by the hand through historical moments such as the creation of the Saffir-Simpson scale or the founding history of Miami, an iconic city vulnerable to hurricanes.

- Jesus Diaz ("Yisus")chef and communicator, shares a traditional recipe of the cuban sandwichas a cultural and tasty closure of this first trip.

In this episode:

- 01:24 What is a hurricane?

- 02:18 Training area

- 03:20 Parts of a hurricane

- 05:25 The eye of the hurricane

- 06:50 The recipe to form a hurricane

- 10:24 Origin of the word hurricane

- 13:47 Sahara dust

- 14:30 Formation of a hurricane

- 16:40 Who moves the hurricanes?

- 22:00 The path of a hurricane

- 27:00 Coriolis force

- 31:00 Hurricanes in Hawaii

- 33:00 The longest hurricanes in history

Hurricanes, squalls and tornadoes: why are they not the same?

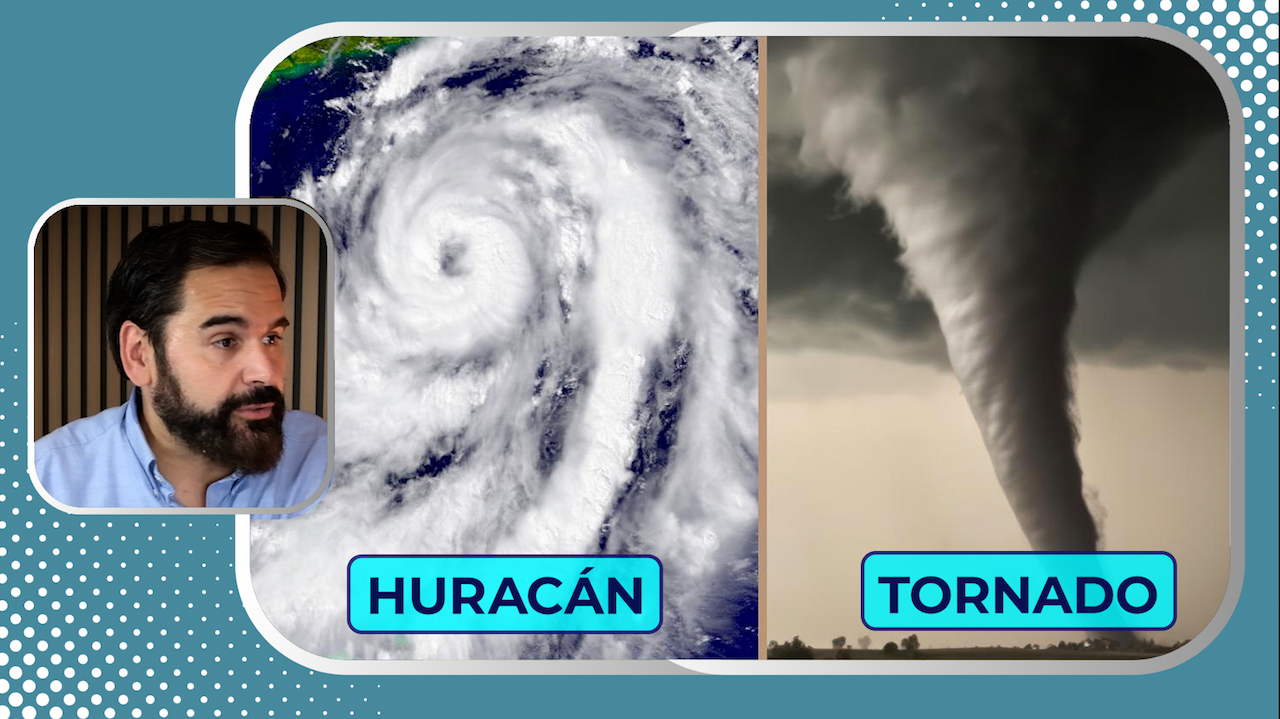

A hurricane is a type of tropical cyclone: a large-scale storm that forms over warm waters and has an organized structure with an intense wind system. Although all tropical cyclones share a similar structure, they only receive the name "hurricane" when their sustained winds are in excess of 74 miles per hour (119 km/h).

The structure of a hurricane consists of three main parts:

- The eyeThe central zone is calm, where the skies may even be clear.

- The wall of the eyeThe most violent ring of the system, where the strongest winds and the most intense rainfall are concentrated.

- Rain bandsThe storm is a spiral system that surrounds the system and feeds the storm with humidity and energy.

Often confused, these phenomena are distinct in nature. The squalls are low pressure systems that can form on land or at sea, both in tropical and temperate zones. The tornadoesOn the other hand, they are extremely localized and short-lived columns of rotating air. On the other hand, the hurricane is born only in tropical oceans, needs warm water as a source of energy, and can last for days or weeks traveling thousands of kilometers.

The origin of the name "hurricane": deities, myths, and power.

One of the most fascinating segments of the episode of Atmospheric Turbulence is the one that explores the etymology of the word "hurricane". The term comes from the language Tainospoken by the native peoples of the Caribbean, such as the Tainos of Puerto Rico, Cuba or Hispaniola. They named "Juracán" to the god of chaos, storms and destruction. When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in America in the 15th century and witnessed these gigantic storms, they adopted the word and Spanishified it as hurricane.

The interesting thing is that this idea also existed in the Mayan mythologywhere Hurakan was the name of a god of the wind and storms, even mentioned in the Popol Vuhthe sacred book of the Maya. According to the myth, it was a one-legged deity, which gave rise to the concept of "the one who limps" or "the one who moves erratically", which is curious considering the unpredictable turns that real hurricanes often make.

Where are they formed and how do they move?

The majority of Atlantic hurricanes are born out of tropical waves that leave North Africa, cross the ocean and, if they encounter favorable conditions (warm waters, low shear, high humidity), evolve from disturbances to tropical storms and finally to hurricanes.

The trade winds and the North Atlantic anticyclone push these systems westward, directing them toward the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, or the east coast of the United States. Along the way, they can intensify rapidly if oceanic and atmospheric conditions permit.

Curiously, hurricanes do not cross the equator. This is due to the Coriolis forcea property of the Earth's rotation that allows these systems to rotate. Near the equator, this force is practically zero, which prevents the rotation necessary for a tropical cyclone to organize itself.

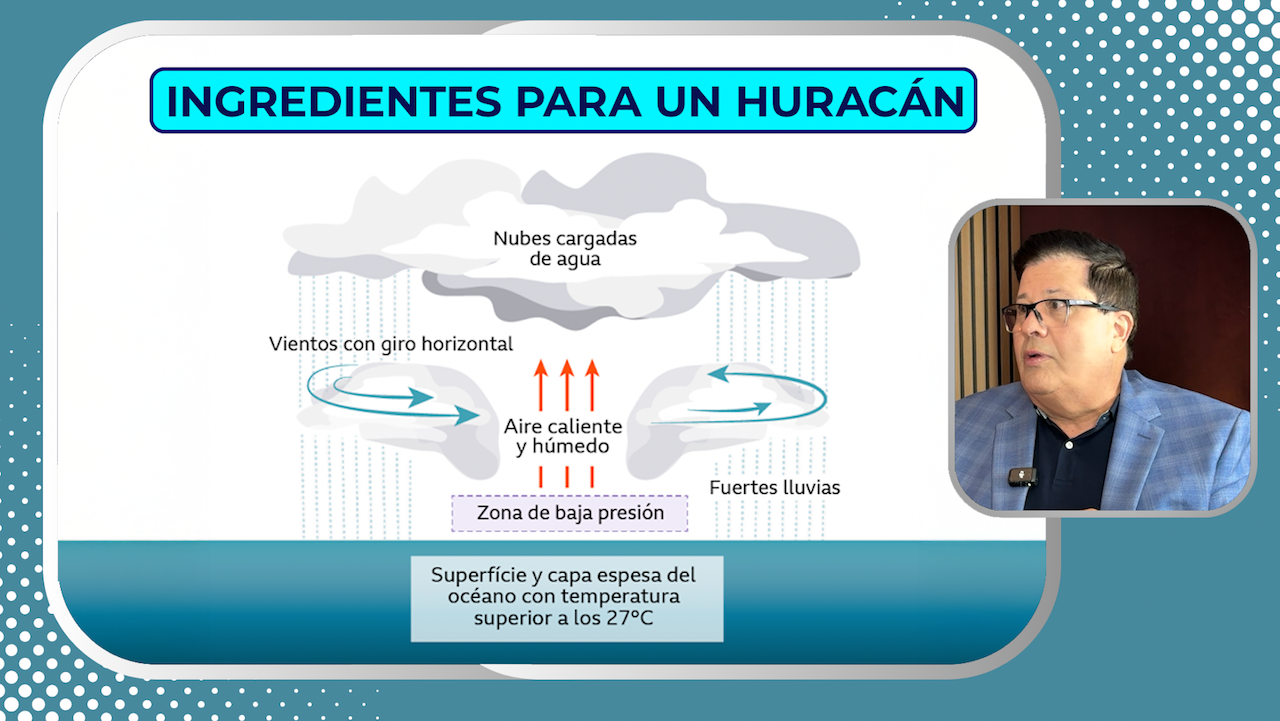

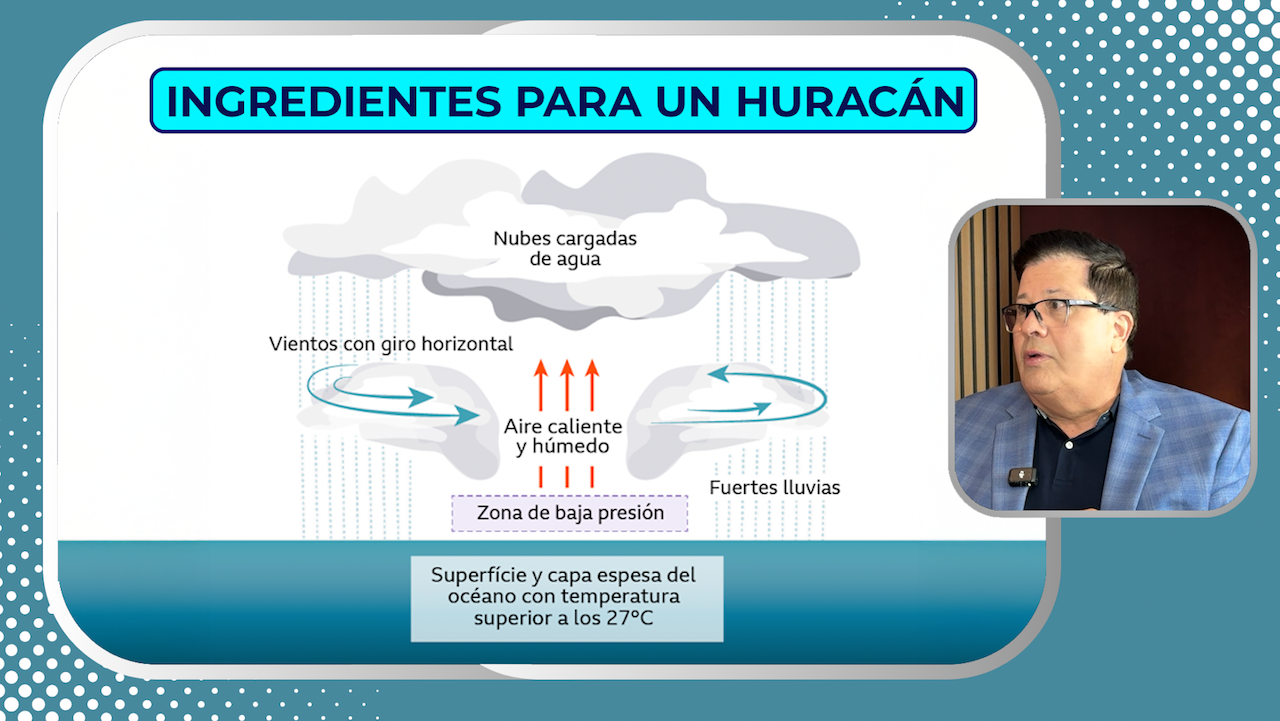

The monster's fuel: the ocean

The main source of energy of a hurricane is the latent heat released when the water vapor condenses in the clouds of the system. This vapor comes from the warm sea, so the minimum threshold water temperature for its formation is usually around 26-27 °C (79-81 °F). But it is not only the surface temperature that matters, it is also the depth of the warm water layer. If the ocean is warm only in the first few meters, the hurricane cools it rapidly. But if the warm layer extends more than 100 or 200 meters, the system can strengthen without limit.

Sahara dust: an invisible enemy

One of the elements that is less known to the general public is the Sahara dustwhich crosses the Atlantic from Africa every summer and can inhibit the formation of hurricanes. This dust:

- Enter dry air in the atmosphere, which cuts off the supply of moisture.

- It is accompanied by cutting winds that "unclutter" the systems under formation.

- It reduces visibility and changes the dynamics of solar radiation.

Although it seems contradictory, this desert dust is one of the great allies of the less active hurricane seasons.

The role of climate change

One of the most relevant points of the last few years is how the global warming is affecting hurricane activity. While the total number of hurricanes may not be increasing significantly, the proportion of intense hurricanes (categories 3, 4 and 5) is increasing..

With increasingly warm oceans and deep layers charged with energy, hurricanes:

- See intensify fastersometimes in a matter of hours.

- They maintain their strength longer even after making landfall.

- They move more slowly, which increases the risk of flooding.

This new hurricane profile poses enormous challenges for the preparedness and response of vulnerable communities, especially in the Caribbean, Central America and the southern United States.

A storm can turn the world upside down

In a final exercise of imagination, the episode raises a surprising idea: a disturbance originating in Africa can develop into a typhoon in Asia. Although this rarely occurs, systems can:

- Cross the Atlantic and reach the Caribbean.

- Landfall in Central America.

- Reorganize in the Pacific and change its name.

- Continue to the western Pacific, where they are monitored by the Japanese weather service and are renamed typhoons.

This global journey illustrates not only the magnitude of these storms, but the need for international cooperation to monitor them and act in time.

🎧 First audio episode now available at buzzsprout.

Follow us on social networks: @AlbertElTiempo | @CanalMeteo